Dolly Jørgensen was a keynote speaker at the Association of Critical Heritage Studies 2020 conference. Her keynote titled “The Remains of Extinction” is available to view. A transcript of the talk is also available.

Naming Extinction

Dolly Jørgensen gave a talk in the virtual Climate Change & Data Storytelling event hosted by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities in May 2020. Her talk “Naming the Victims of the Sixth Mass Extinction” is available to watch here.

Climate Heritage Workshop

Aarhus University and the EU Life Program project Coast 2 Coast Climate Challenge (C2C) organized an event titled “Climate Heritage: Climate change and its relation to cultural/natural heritage” in March 2019.

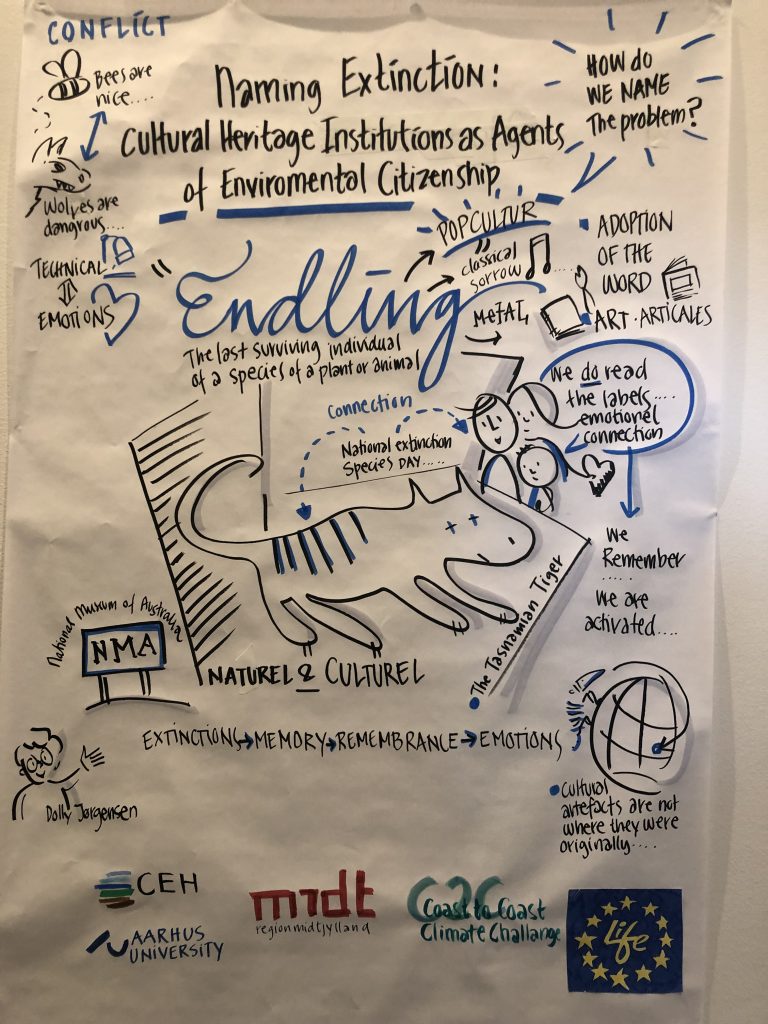

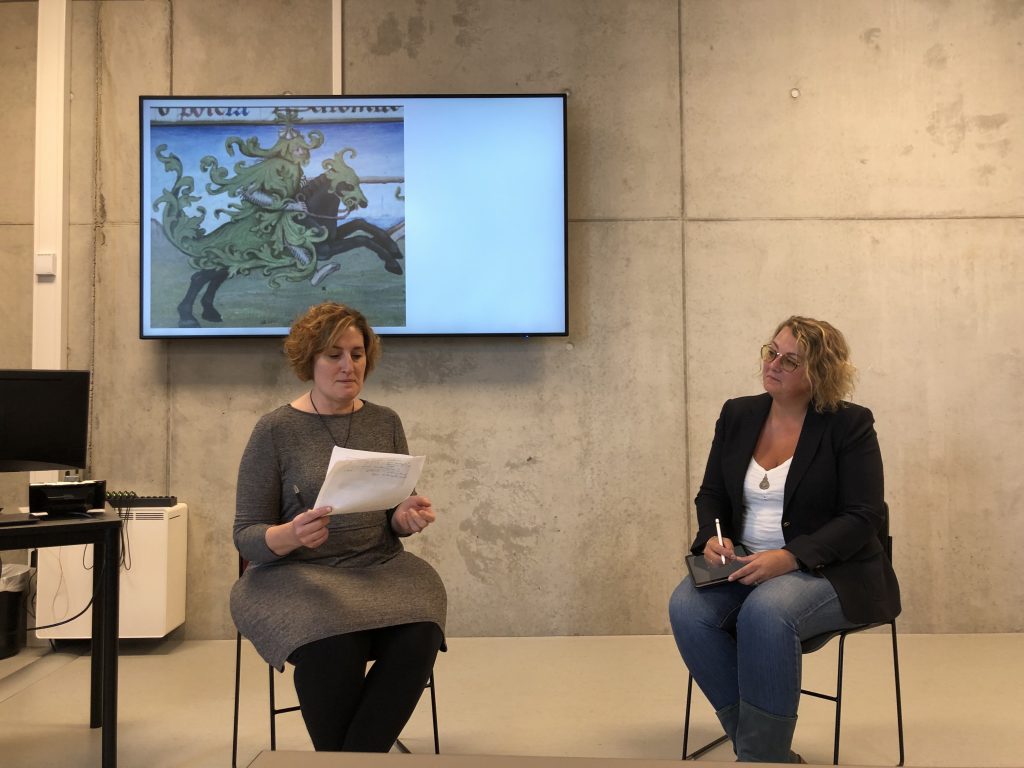

Dolly Jørgensen was one of six keynote speakers at the event, which focused on the complex relationships between heritage and climate change, and the way a changing climate affects our natural and cultural heritage. Her keynote titled “Naming Extinction: Cultural Heritage Institutions as Agents of Environmental Citizenship” focused on how cultural heritage institutions can create meaningful narratives around extinction that potentially lead to more aware citizens of the planet.

A booklet summarising the event and the presentations is available for download. You can also see videos of the presentations online.

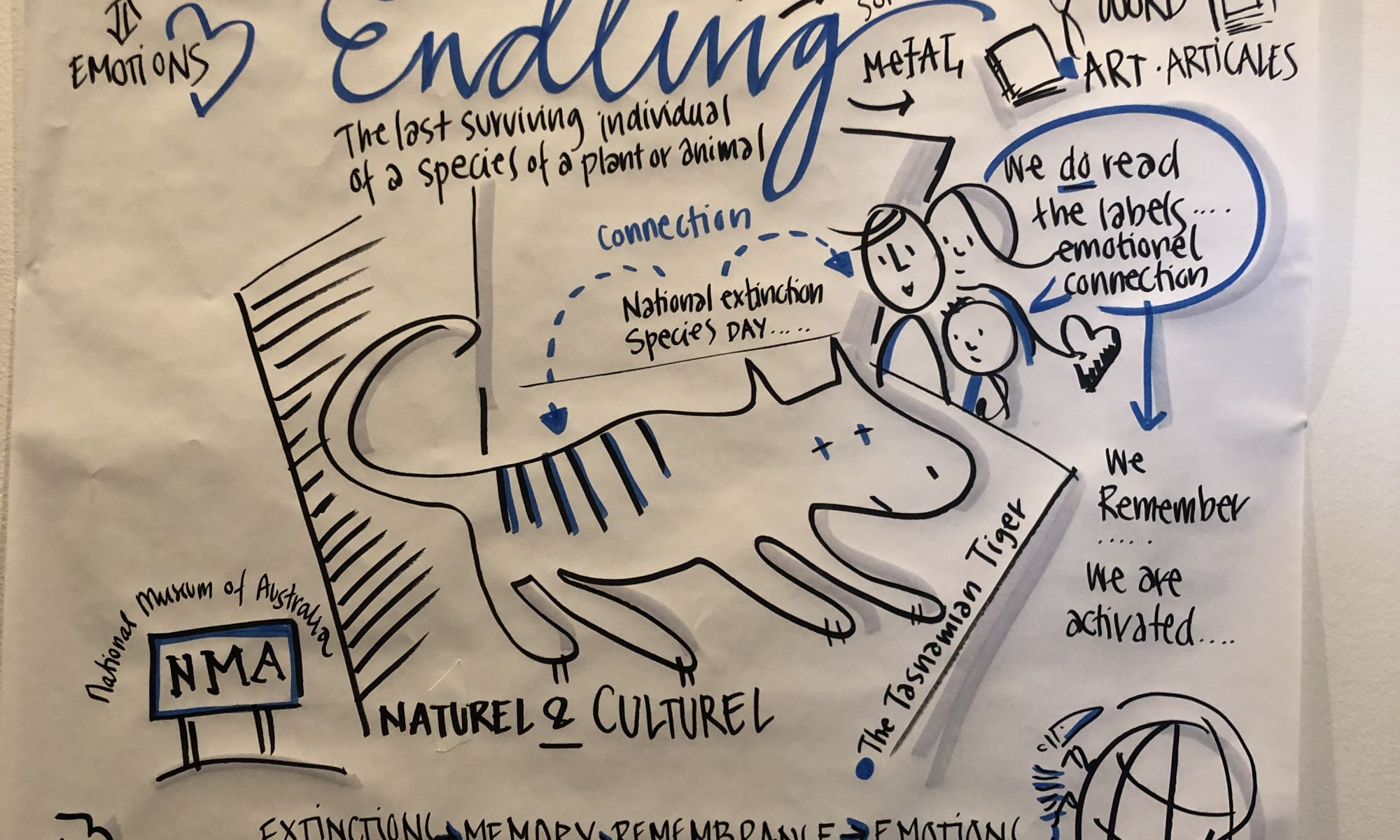

One of the most innovative parts of the event was the use of a graphic artist to record the content of the talks in real time — without having seen any notes in advance! It was quite impressive, as you can see from the graphical representation of Dolly’s talk below.

Museums and Environmental Humanities Course

The Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs project was involved in a 5-day PhD level course titled “Museums and Environmental Humanities: A Master Class” held in Stavanger, Norway, in August 2019. Each day featured a lecture, a master class with student presentations of an object from their research, and a visit to a local museum. Museum personnel were involved throughout and curators participated in the discussion sections with the students.

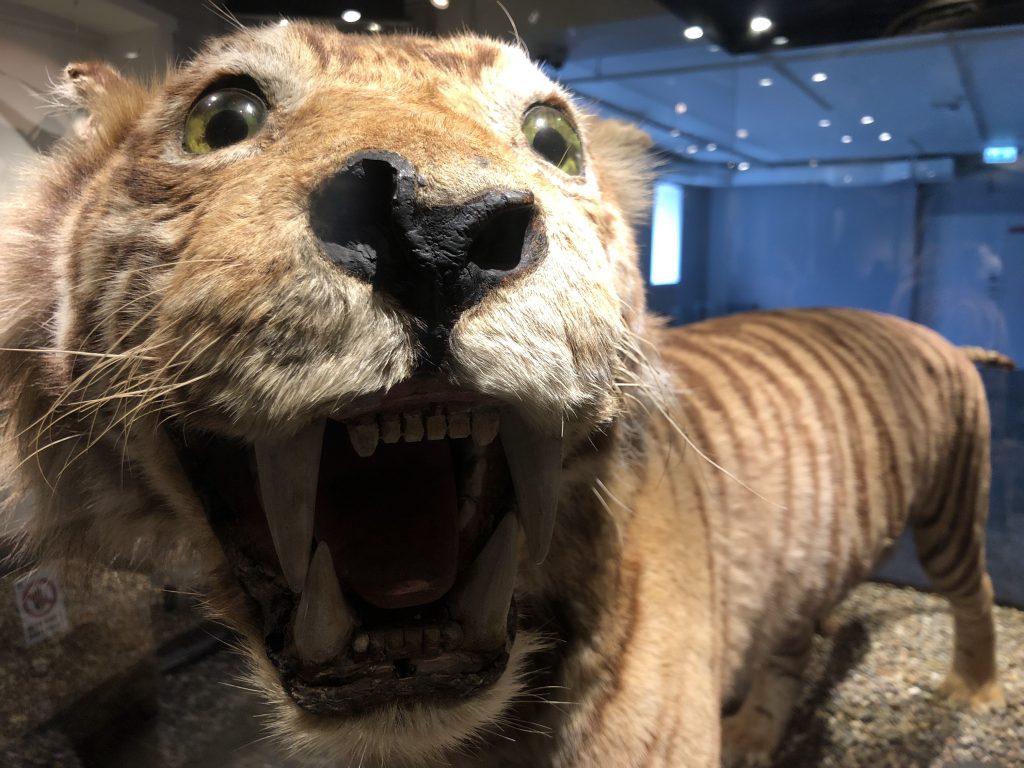

PI Dolly Jørgensen gave the Day 1 lecture “Portraits of extinction: Encountering extinction narratives in natural history museums”. That day the students got to explore the Stavanger Museum and its collection of natural history specimens, including an extinct tiger sub-species.

Students exploring the gallery

The Javanese tiger

On Day 2, Henry McGhie, who was previously at the Manchester Museum and organized our Extinction as Cultural Heritage project kick-off meeting there, spoke on Day 2 on “The role(s) of museums in a changing climate”. We visited the Norwegian Petroleum Museum and their new Climate for Change exhibit.

Exploring the local and global causes and consequences of climate change

Seeing how “heavy” the carbon footprint of different people are

Day 3 featured a lecture “The Anthropocene: a new epoch to think with in museums” by Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs advisory board member Libby Robin. One of the student presentations that day even featured extinction–Anna-Katharina Laboissière presented her idea “The good death: reframing extinction?” The group visited the Flora: Between People and Plants special exhibit at the Stavanger Art Museum

We were out at Vitengarden in the countryside on Day 4. Brita Brenna from University of Oslo talked on “The naturecultures of fieldwork in the Arctic” and the students got to explore naturecultures of the fields of Jæren in the agricultural collections.

The final day started with another Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs advisory board member: Karen Rader gave her lecture on “Thoughts in Things: a history of science perspective on museums in transition”. The visit that day involved two museums: The Norwegian Canning Museum and the Maritime Museum.

The master class session with lecturer Karen Rader and student Anne Mette Seines

Great sardine packing job by Faizah Zakaria at the Canning Museum

This event showed the fruitfulness of using environmental humanities approaches when thinking about how to display and interpret objects and social concerns.

Museum narratives are not neutral

The Remembering Extinction project is concerned with the ways we narrate extinction histories and extinction future avoidance, particularly in museum settings. Because of that interest, I always pay attention to how narratives in museums are constructed.

When I visited the Moesgaard museum in Aarhus, Denmark, this week, the presented narrative of evolution in the Evolutionary Staircase struck me as particularly problematic. The staircase presents the change over time in humanoid species as an entry point to its archeological exhibits. In so doing, it is also dealing with the extinction of some ancestral species to modern humans (Homo sapiens).

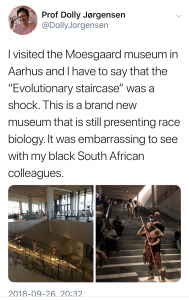

I tweeted about this display and its racial overtones.

Because of my tweet, I received an invitation from the Moesgaard museum to further explain my concerns in a longer format. I share with you here the letter I wrote and sent to the Head of Exhibitions at the museum:

Dear Head of Exhibitions,

I was invited via a twitter exchange with the Moesgaard museum to explain my concerns about the exhibit in your central staircase (you can see my original tweet here). I visited the museum on Wednesday, 26 September, with four South African academic colleagues (three of African descent and one of settler descent). They were visibly aghast at the exhibit, as was I. This is why I, as an academic who analyses museum exhibition narratives, tweeted about the shocking presentation.

Let me start by saying that I understand that the individual models which have been displayed are based on accepted scientific findings – that is not my concern. What is concerning is that the display of those scientific findings has created a narrative that very clearly reinforces racial biology.

As I hope you are aware, the Scandinavian countries along with the rest of Europe have a long history of participation in biological sciences which attempted to explain “scientifically” why non-white peoples were inferior to white people. That argument rests on an idea that white skinned populations are more “civilised” than others and looks for morphological (as well as cultural) differences to explain why this is so. This is not an “old” argument — a 2018 study in Sweden showed that racial experiments on Sami continued into the 1950s.

With that in mind, look at the exhibit at Moesgaard. It very clearly shows dark skinned humanoids beginning with Lucy in Ethiopia getting lighter and lighter to the bottom where full-fledged homo sapiens is represented by a white Koelbjerg Man from Denmark. While these are individually true archaeological findings, the museum has created a spatial and temporal narrative through the display which has been labelled “Evolution”. This version of Evolution shows a movement from black to white. The museum has chosen specific findings to display out of a myriad of possibilities, and the choices have been constructed in a way which sits well with the arguments long espoused by racial biology. As a scholar working on the construction of narratives in museum displays, this is striking.

This narrative with light-skinned as the end point of evolution is not the only one which could have been constructed. Instead of ending on the Koelbjerg Man, the museum could have instead shown concurrently a variety of human finds from the Stone Age across the world – which would have clearly shown diversity in skin tones. It is not as if the museum is showing all Denmark specimens – you start with Lucy from Ethiopia and move through global finds before then. So why limit the conclusion of evolution to a find from Denmark? By making this choice, the museum is clearly aligning itself with a narrative of evolution that puts lighter skin higher on the evolutionary ladder.

Museums are never neutral. The way we display our science in museums tells a story to the visitor. And whether it was intentional or not, the story told in this particular exhibit is that human evolution progresses from dark to light. This is a dangerous narrative to reinforce.

Kindest regards,

Dolly Jørgensen

Professor of History