Project funded by Formas, The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, 2017-2019

Project leader: Finn Arne Jørgensen, Umeå University.

Collaborating institutions: Department of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies, Umeå University; HUMlab, Umeå University; Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies, SLU Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Recreational uses of outdoor natural environments have become a fundamental part of Scandinavian national identities since the late 1800s. Through leisure activities like trekking and hunting, people gain access to particular ways of knowing and valuing nature, developed over time as cultural traditions. More than anything else, such activities have come to define what a natural landscape should look like and how it should be valued. This project seeks to understand what happens when new and pervasive digital technologies become part of this relationship with nature.

Today, digital devices have become an integral part of many ways of using nature for leisure purposes. For instance, hunters and trekkers alike use GPS units and digital maps for planning, navigating, and sensing landscapes. Cell phones enable instant communication across distance, but also provides extensive information search and documentation opportunities through a variety of specialized apps. Digital photography allows for instant and virtually unlimited capture of scenic views and moments in nature. Such uses of what we can label media technologies can be seen either as augmenting the use of nature (by providing access to otherwise hard-to-acquire information) or as reducing environmental literacy and spatial cognition capabilities by taking away the need to “read” the landscape in traditional ways. This creates a need for extensive cultural negotiations with and about new technologies and their place in nature.

The goal of the project is to uncover the ways in which media technologies have shaped recreational uses of nature in Scandinavia since the late 1800s. The project will pay particular attention to digital media technologies post-2000, but will apply a comparative historical perspective to place these technologies in a longer historical context. Such a long time perspective is necessary in order to properly evaluate claims about fundamental changes caused by new media technologies in contemporary Scandinavia.

The project will investigate three main research questions:

- How have historical and current media technologies been incorporated into in hunting and trekking traditions in Scandinavia?

- How have media technologies shaped the valuation and management of nature for recreational use in Scandinavia over time?

- How do current recreational users of Scandinavian nature negotiate over the meaning of new technologies in nature?

The project hypothesizes that current debates over new and digital media technologies mirror those that took place with other forms of media technologies in the past. Furthermore, the project expects to find that the role of so-called early adopters of new technologies is critical in defining the status and broader reception of these technologies. Analyzing the gender, class, and social status of these users will thus be a central point of investigation.

Case studies

Through two case studies, the project examines the extensive cultural negotiations with and about new technologies and their place in Scandinavian nature:

1. Trekking, navigation, and media technologies

The first case study will place the project’s research questions in a longer historical perspective, asking how trekkers have used media technologies in traveling and navigating both familiar and unfamiliar landscapes. This case will thus trace the use of media technology in travel genealogically, backwards in time, following the general approach suggested by Michel Foucault (1978) of critically analyzing the present by studying how it has been shaped by historical forces. This historical perspective will add a necessary counterpoint to the narratives of dramatic change and business hype that surround the digitization of space and place.

This case will keep a dual focus on breaking points and continuation, recognizing that what does not change over time can be just as interesting and relevant as what does change. This case will focus on travel routes and delve deep into the ways in which wayfinding, navigation, and the formation of cognitive maps took place in these cases. The project team will identify, analyze, and compare the historical development of these routes as examples of how the landscapes of the Scandinavian countryside became increasingly covered in a dense annotation web of transportation infrastructures and cultural information layers stored in and accessed through media technology. We will pay close attention to the relationship between the mind, the body, and the landscape, and how technologies help mediate this relationship. How did travel along these routes—the sets of instructions, mediating technologies, and infrastructures connecting places—change over time and how did the experience and valuation of the landscape change as a result?

For the historical part of this case, we will analyze written accounts of travel routes and narratives from Sweden and Norway for the period 1850-present. We will identify the media traces of these routes throughout time, through digitizing select routes and areas from travel guides by authors such as Carl Martin Rosenberg (Handbok för resande i Sverige, 1872; Ny reshandbok öfver Sverige, 1887) and Yngvar Nielsen (Reisehaandbog over Norge, published in 12 editions between 1879 and 1912), particularly aiming to trace the spread and transformation of routes as cultural objects over time. These books contain detailed spatial data about routes, including locations, distance, time, transportation modes, and points of interest. At the same time, the authors frequently make very clear statements about the value of particular ways of experiencing landscape, so these books lend themselves to a combination of methodical approaches. We will also use the Swedish and Norwegian Trekking Associations’ annual volumes, published annually since respectively 1886 and 1868. Much of this material has recently become digitized and has yet to be analyzed through digital methods. In the case of Sweden, Projekt Runeberg has digitized almost all of the volumes that are in the public domain (1886-1943) and these are openly accessible online; but there is also vast archival material, such as the 174 shelf meters of archival material from Svenska Turistföreningen in the Swedish National Archives.

The historical study will be brought in dialogue with a contemporary study of the media technology use of trekkers, based on a combination of literature studies of books, magazines, and magazines from the last 20 years with deep, qualitative interviews with trekkers about their media technology usage in Norway and Sweden (the interviews will include early adopters/advanced users, casual users, and perceived non-users of media technology). The Norwegian and Swedish Trekking Associations are also good sources of information here, as they receive considerable feedback from the users of their infrastructures about technological features and support. We will also look at how these associations and other institutional and corporate actors provide technological services, such as apps and digital maps, for their target users.

2. Hunting in the digital landscape

The second case study will examine how visions and practices of digital geospatial technologies have entered into established cultural traditions of hunting in Sweden. Perhaps more than any other individual technology, handheld GPS trackers and digital maps have transformed the experience of hunting. Yet, while scientific uses of radiotelemetry and other forms of animal tracking has been studied (Benson 2010), little has been done on hunters’ integration of such technologies in their practices. Personal navigation, the knowledge of where the hunter and the hunter’s dogs are in relation to the landscape and the prey, has long been key to hunting practices. Today, more and more hunting dogs wear GPS collars, allowing hunters to continuously track their location on handheld units, but also delegating many navigational and relational aspects of hunting to a mediating technology. While the main empirical focus of this case is on hunters’ adoption and use of GPS in their activities since the late 1990s, we will place it within a longer historical timeframe to properly understand how the practices and arrangements were established.

This case examines the integration of informational media, digital communication, and navigation technologies into moose hunting practices in Scandinavia. Hunting has always relied on tools that are intrinsic to its practice. These tools enable action at a distance (spears, arrows, guns), but also the exchange of information between hunters, prey, and domesticated hunting animals such as dogs. These hunting animals might also be considered a kind of mediator, translating and transmitting relations of landscape and prey for their spatially- bound operators, who uses the animals as part of a mental visualization of the movements of prey. However, hunters have increasingly integrated media tools such as tiny video cameras and GPS transmitters that can extend, enrich, and quantify these predatory relations. This case explores how such devices find their way into—and how we might use them to understand—the multisensory mediated landscapes of hunting. What were the consequences for the way hunters know and value nature, negotiating between “tradition” and “authenticity”?

At a practical level, this case will combine qualitative interviews and fieldwork observation with extensive textual studies collected from archives, media databases, and libraries. The Swedish Hunters’ Association, established in 1830, will be a valuable source through their own archives as well as their journal which dates back to 1908. Many hunters have also been active in nature protection groups such as Naturskyddsföreningen, which was established 1909 and issues a journal, Sveriges Natur, and in culture protection organizations such as Hembygd and its local associations such as Hembygda in Jämtland. Similar associations exist in Norway, providing a rich and extensive archive material that can be examined. The records and journals of these associations contain significant historical information where change over longer time periods become visible. An ethnographic survey of online discussion forums dedicated to hunting, as well as a review of advertising material in hunter magazines, will also be part of the textual studies.

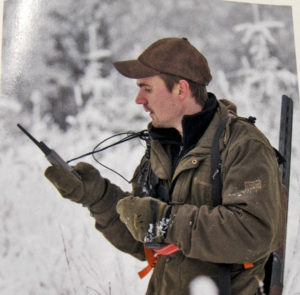

The textual studies will be complemented with fieldwork observation and interviews, bringing ethnological approaches into the project. We will observe two hunting teams during the course of the project, in September 2017 and 2018. We will study the relationship between hunters and GPS-collared dogs, particularly how both parties negotiate their relationship as they move through the landscape. All hunters and dogs in the team will be tagged with simple and affordable GPS loggers that track their location at all times. This part of the study will be similar in design to Brøseth and Pedersen (2000), who tagged the human participants in a ptarmigan hunting team. After the hunt, the resulting high time-resolution dataset for limited geographic areas, will be used to to create animated visualizations of the movements of the team, displayed on a digital map (using standard GIS software). We will also use GPS-tagged photographs actively in the documentation of the fieldwork. The resulting visualization will combine both GPS logs and photographs, and is a critical component of the fieldwork analysis. This active use of GPS sensors in this case is part of a larger debate on retooling the humanities through critical engagement with technology. We believe that this material engagement with sensory and geolocative technology is an essential component of humanistic inquiries into the nature of technology and its uses in historical scholarship. Such approaches have not been extensively explored previously in social science nature research, so the project has potential for considerable methodological innovation.

For more information about the project, contact Finn Arne Jørgensen at fa@jorgensenweb.net.

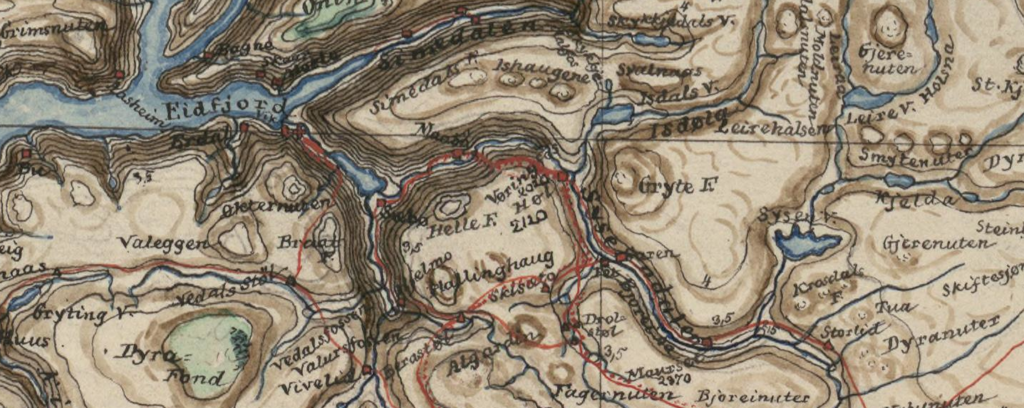

Header image: Peter Andreas Munch: «Kart over Fjældstrakten mellem Hardanger, Voss, Hallingdal, Numedal, Thelemarken og Ryfylke». Scale 1:500000, published in Peter Andreas Munch, «Indberetning om hans i somrene 1842 og 1843 med Stipendium foretagne Reiser gjennem Hardanger, Numedal, Thelemarken m.m.», Ms. fol. 1250, National Library of Norway. Public Domain.