Dolly Jørgensen was a keynote speaker at the Association of Critical Heritage Studies 2020 conference. Her keynote titled “The Remains of Extinction” is available to view. A transcript of the talk is also available.

Naming Extinction

Dolly Jørgensen gave a talk in the virtual Climate Change & Data Storytelling event hosted by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities in May 2020. Her talk “Naming the Victims of the Sixth Mass Extinction” is available to watch here.

Call for Papers for Extinction in Public

Extinction in Public, A Symposium at Manchester Museum, October 15–16, 2020

What do we talk about when we talk about extinction? As a concept, a process, and a specific event, as something troublingly natural and social, as both an observable but mostly unrecorded phenomenon, “extinction” carries competing and contradictory meanings. Yet in the current conjuncture, extinction operates as an emergent keyword of public life. Charged with new immediacy by the cascading effects of climate collapse, mobilised by the collective power of street movements such as Extinction Rebellion and Ende Gelände, and theorised by the nonhuman turns of the environmental humanities, Anthropocene, and multispecies studies, extinction can no longer be contained within the cabinets of natural history museums – if indeed it ever could.

But extinction means different things to different publics. It is a polysemous concept, even slippery. For some, extinction denotes an explicitly human concern and provokes a species-level apocalyptic image of the end of humanity. For others, extinction is more closely associated with the slow passing of charismatic nonhuman animals, conjured evocatively in the image of the endling. The Sixth Mass Extinction Event is itself overwhelming in its valences, not just because it invokes a staggering loss of fungal, plant and animal wildlife, and not just because it comprises an equally staggering loss of indigenous languages, cultures and practices. It is overwhelming, too, because it calls on “us” to think carefully about “our” own complicities and contributions to its continuation, without ever losing sight of the vastly unequal social relations which produce its globally uneven and differentiated impacts.

At the same time, extinction remains elusive and contested. Although the IUCN Red List is forever developing its catalogue, the statistics of extinction vary, and most individual species extinctions remain unrecorded and unknown. Although the predominant signifiers of extinction are still associated with polar bears and whales, it is in fact invertebrates that bear the brunt of anthropogenic impacts. And although many see global heating of 2°C as the ecological tipping point for the planet, indigenous peoples have long understood that “we” have already crossed a “relational tipping point”, as Kyle Powys Whyte suggests. Settler colonialism and capitalist modes of production have broken cross- species kin relationships that were previously foundational to planetary stewardship.

This symposium aims to develop critical perspectives on the sixth extinction. By adopting the title Extinction in Public, we mean to draw attention to and critically reflect on the ways in which extinction – in all of its contradictory meanings – is currently being made public. What is at stake in making public the Sixth Mass Extinction Event? Which publics are engaging with extinction? And what does it mean to them? By hosting this symposium in Manchester Museum, a museum that is exploring its own role in communicating

extinction to different audiences, we especially want to interrogate the relationship between public institutions, public participation, and anthropogenic extinctions, opening up new ways of thinking extinction in the museum space.

We seek abstracts which intervene in the discourse of extinction. We welcome papers which engage directly with the following concerns, but we are also open to hearing about projects which approach extinction in other ways.

- Affects, feelings and emotional registers: What do different publics feel about the sixth extinction? What are assumed to be the appropriate emotional responses to language death and biotic species loss? And how are these responses enacted by different publics? What is it like for people to be living through the Sixth Mass Extinction Event as an event? How does anthropogenic extinction inflect foundational theorisations of mourning and melancholia? What sort of dialectics between urgent action and reflective pause are being struck around the world? What are the risks and rewards of making room for queer, ironic, irreverent, antipathetic or even ambivalent responses to extinction, and in which cases do these putatively “bad environmentalisms” – as Nicole Seymour terms them – generate innovative, empowering and critical opportunities for grappling with climate change? How can we cultivate what the late Deborah Bird Rose called “love at the edge of extinction”? And what is the role of performance, ceremony, or ritual practices in engaging with extinction?

- Heritage, museums, and exhibiting extinction: What do people expect to see when they visit a museum exhibit on extinction, and how are museum workers transforming heritage practices in a time of anthropogenic extinction? If the prevailing position of the museum has been one of “authoritative neutrality”, as Robert R. Janes puts it, then how is the sixth extinction affecting the ways in which museums engage with different publics? How might museums and social movements jointly intervene in the climate emergency? Moreover, because the modern museum is founded on forms of extractivism and imperialism, is human and nonhuman justice to be found in the re-presentation or repatriation of long- exhibited objects? Put differently, is it possible for museums to heal environmental and historical injustices by “de-growing” their collections, as Jennie Morgan and Sharon MacDonald suggest? What sort of futures do museums envisage for life on the planet, and how can heritage play an active role in a time of climate emergency?

- Conceiving, theorising and delimiting extinction: What sort of vocabulary can we draw from in order to make sense of the Sixth Mass Extinction Event, and what vocabulary might we need to recover or invent? How useful is the ongoing debate between Anthropocene/ Capitalocene/ Plantationocene for engaging different publics in extinction? Recent interventions into extinction by Ashley Dawson and Troy Vettese have reinvigorated key Marxist concepts such as the commons, accumulation and formal and real subsumption. Which other critical concepts might help us think through extinction? Can the Sixth Extinction be understood through the many advances of ecofeminist thought (Merchant, Plumwood, Mies, Shiva)? How to build on Juno Salazar Parreñas’ recent project to decolonise extinction?

- Political economies, radical insurgencies: Extinction always marks an end, but it also opens up new possibilities for political action. On the darker side of possibility, what mutations of ecofascism and climate Malthusianism are already developing? How does the prevailing neoliberal order speculate on endangered life, turning extinction into profit? And what are we to make of misanthropic political responses to biodiversity loss, such as the movement towards “voluntary extinction”? Even so, if the main driver of the Sixth Extinction is habitat loss, and is thus a question of land-use, then how might society and land be organised otherwise? And if the extinction crisis is at once an environmental and social justice issue, how can social movements and conservationists build collective power together? Does the “Extinction” in “Extinction Rebellion” mean the same thing to each of its members, and what does extinction mean to XR’s critical friends and opponents?

Please send extended abstracts (maximum 500 words) and short biographies for 30- minute papers to Dr Dominic O’Key (D.E.OKey@leeds.ac.uk) by 10th March 2020.

In an effort to support and develop more sustainable academic practices, this symposium is a “No Fly” conference. Our budget will cover (within reason) contributors’ subsistence, accommodation and land-based travel to and from Manchester. We welcome remote participation, and will endeavour to make digital conversations a meaningful part of the symposium.

New article on rhetorics of extinction & de-extinction

Dominic O’Key, post-doctoral research fellow with the University of Leeds team on the EXTINCT project, has published a new article proposing that the novel Pterodactyl, Puran Sahay, and Pirtha by Mahasweta Devi works through literary de-extinction, which he defines as “any creative attempt to reimagine extinct species within the here and now a text’s narrative time.” Read his article here.

“By lifting the extinct figure of the pterodactyl out of the archives of the fossil record and into the world of this short novel, Mahasweta dramatizes how Puran becomes touched by the dactyl, or finger, of an entire nonhuman history which at the same time remains other to him. … By refusing an archival desire to catalog and commodify life, Mahasweta’s short novel re-imagines de-extinction as a model for opening literary form to the nonhuman and returning us to the present as a site of political and ecological resistance. In this respect, I see Pterodactyl as both a challenge to contemporary biotechnological conservation projects and a marker of how postcolonial literature can offer a multispecies intervention into the sixth extinction.”

Dominic O’Key (2020) “Entering Life:” Literary De-Extinction and the Archives of Life in Mahasweta Devi’s Pterodactyl, Puran Sahay, and Pirtha, Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 31:1, 75-93, DOI: 10.1080/10436928.2020.1709715

New article “Extinction and Agricultural History”

Dolly Jørgensen has published a new article on extinction as part of a Roundtable on the topic “Why does Agricultural History Matter” in the journal Agricultural History. In her contribution “Extinction and Agricultural History”, she argues:

The decline of wild species and the increase in domesticated ones is fun- damentally an agricultural issue, and this is where agricultural history comes into play. If humans are to create futures for threatened species different than those projected by the IPBES report, we need to understand how our present extinction situation is tied to long-term patterns of agricultural production and consumption. Agricultural historians are perfectly positioned to analyze these linkages between food production and biodiversity destruction, especially in light of the ongoing work by agricultural historians to explicitly engage with environmental issues in conjunction with the much younger field of environmental history.

You can read the entire roundtable here.

Citation for the article: Dolly Jørgensen, “Extinction and Agricultural History,” Agricultural History 93, no. 4 (2019): 690-694.

Climate Heritage Workshop

Aarhus University and the EU Life Program project Coast 2 Coast Climate Challenge (C2C) organized an event titled “Climate Heritage: Climate change and its relation to cultural/natural heritage” in March 2019.

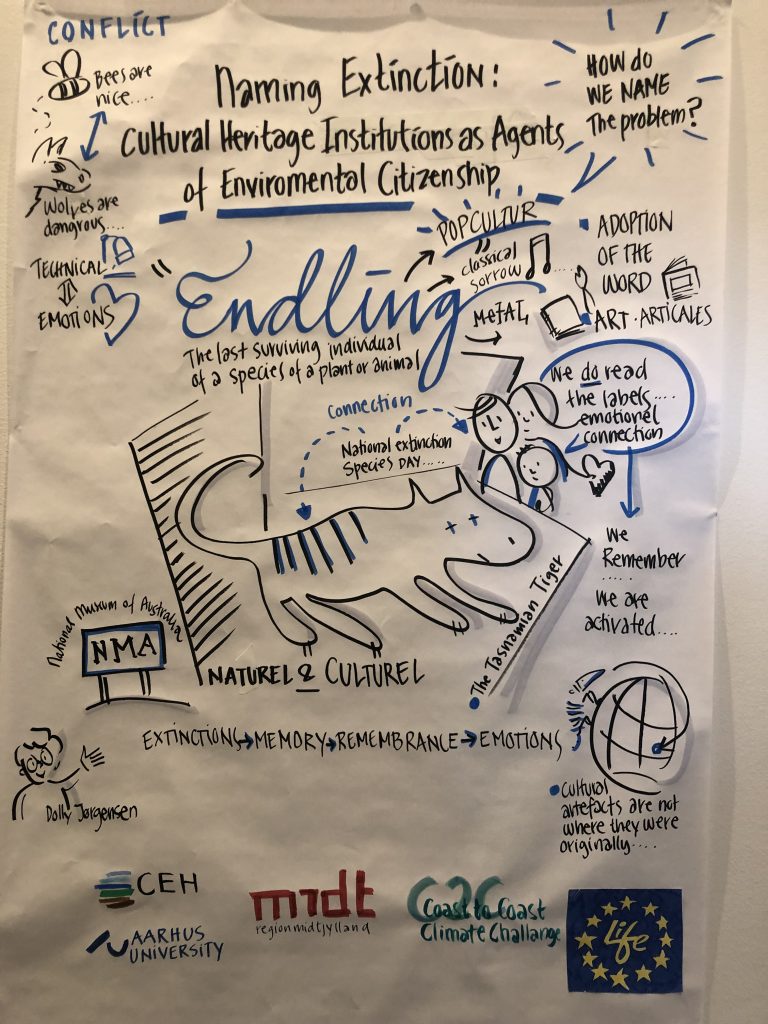

Dolly Jørgensen was one of six keynote speakers at the event, which focused on the complex relationships between heritage and climate change, and the way a changing climate affects our natural and cultural heritage. Her keynote titled “Naming Extinction: Cultural Heritage Institutions as Agents of Environmental Citizenship” focused on how cultural heritage institutions can create meaningful narratives around extinction that potentially lead to more aware citizens of the planet.

A booklet summarising the event and the presentations is available for download. You can also see videos of the presentations online.

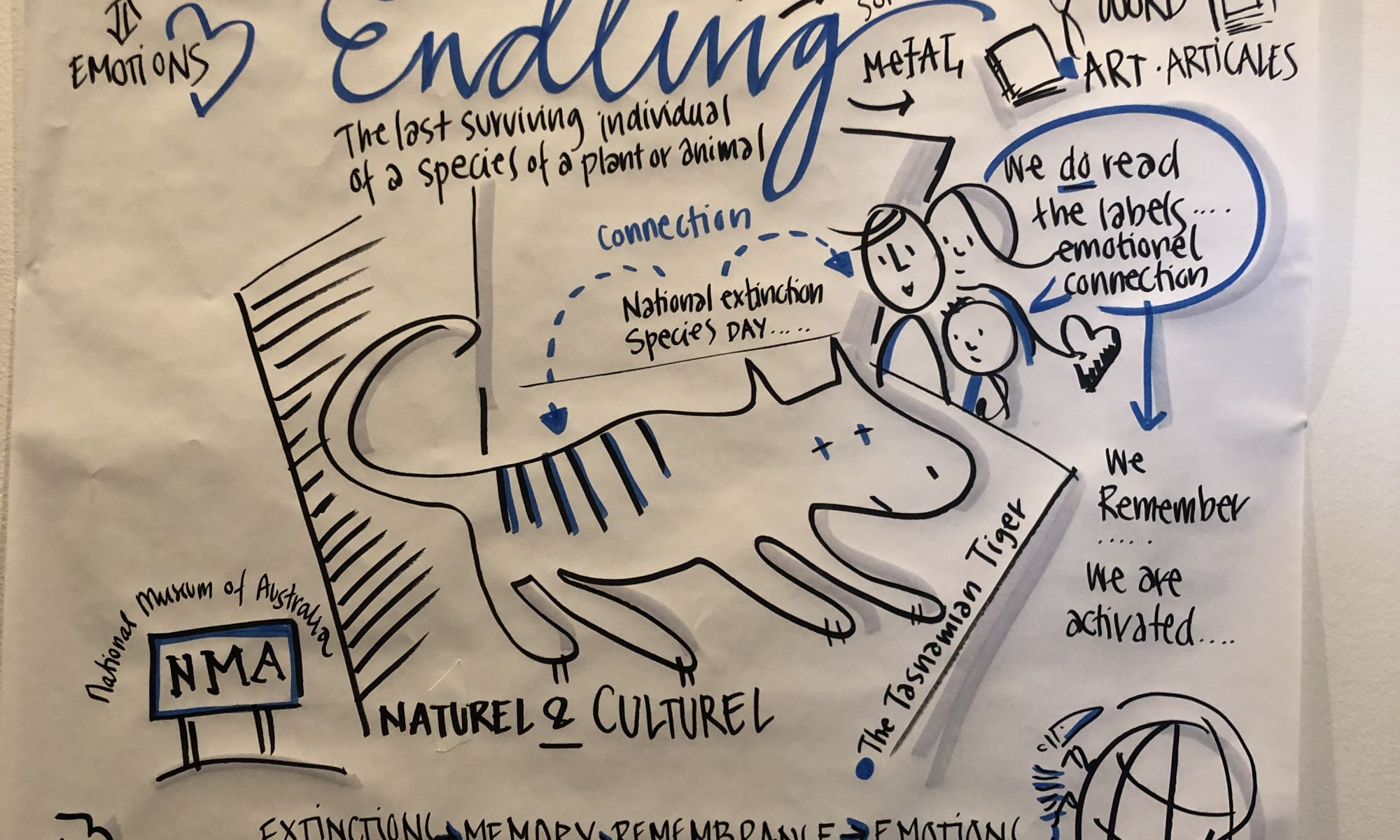

One of the most innovative parts of the event was the use of a graphic artist to record the content of the talks in real time — without having seen any notes in advance! It was quite impressive, as you can see from the graphical representation of Dolly’s talk below.

Two news articles feature emotions and extinction

PI Dolly Jørgensen’s research on the emotions tied to extinction and attempts to bring back species like the beaver was featured in two articles published in September 2019.

These appeared in Tidningen Curie, the blog of the Swedish Research Council (VR) and the website for the national Research Days (Forskningsdagene) run by the Norwegian Research Council (NFR):

New team members

The Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs team has expanded.

Gitte Westergaard joined the team as a PhD student in February 2019. She will be working on her PhD dissertation, tentatively titled An Exploration of Island Extinction through Museum Collections: Towards a Decolonization of Animal Remains through January 2023. Her case studies include endangered lemurs collected by missionaries to Madagascar, tortoises considered the last of their kind on display, cultural artefacts made out of feathers from the extinct Hawaiian ʻōʻō bird, and endemic and invasive rats in the Caribbean. Gitte earned her Masters degree in Sustainable Heritage Management from Aarhus University in 2018.

Verity Burke joins the team in October 2019 as a postdoctoral research fellow for two years. She has a PhD in English Literature from University of Reading (2018). She is currently a postdoc on the AHRC-funded project “Narrativising Dinosaurs: Science and Popular Culture from 1850 – present” at University of Birmingham. She will be focusing her studies for this project on two exhibits at the Natural History Museum (London).

Museums and Environmental Humanities Course

The Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs project was involved in a 5-day PhD level course titled “Museums and Environmental Humanities: A Master Class” held in Stavanger, Norway, in August 2019. Each day featured a lecture, a master class with student presentations of an object from their research, and a visit to a local museum. Museum personnel were involved throughout and curators participated in the discussion sections with the students.

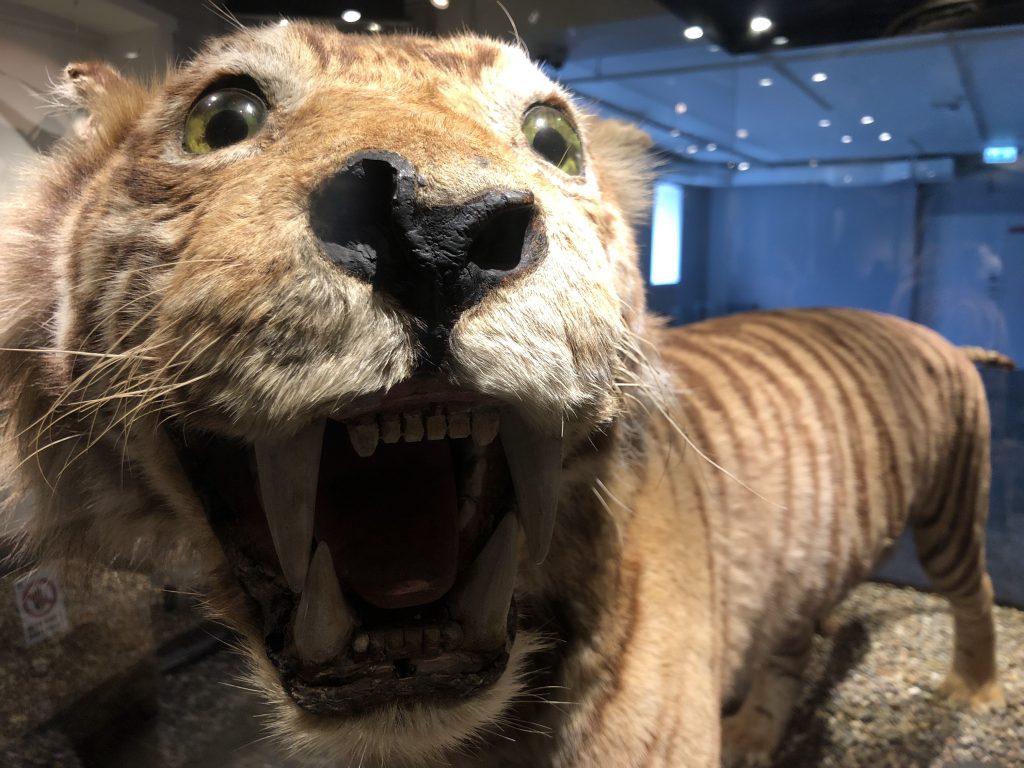

PI Dolly Jørgensen gave the Day 1 lecture “Portraits of extinction: Encountering extinction narratives in natural history museums”. That day the students got to explore the Stavanger Museum and its collection of natural history specimens, including an extinct tiger sub-species.

Students exploring the gallery

The Javanese tiger

On Day 2, Henry McGhie, who was previously at the Manchester Museum and organized our Extinction as Cultural Heritage project kick-off meeting there, spoke on Day 2 on “The role(s) of museums in a changing climate”. We visited the Norwegian Petroleum Museum and their new Climate for Change exhibit.

Exploring the local and global causes and consequences of climate change

Seeing how “heavy” the carbon footprint of different people are

Day 3 featured a lecture “The Anthropocene: a new epoch to think with in museums” by Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs advisory board member Libby Robin. One of the student presentations that day even featured extinction–Anna-Katharina Laboissière presented her idea “The good death: reframing extinction?” The group visited the Flora: Between People and Plants special exhibit at the Stavanger Art Museum

We were out at Vitengarden in the countryside on Day 4. Brita Brenna from University of Oslo talked on “The naturecultures of fieldwork in the Arctic” and the students got to explore naturecultures of the fields of Jæren in the agricultural collections.

The final day started with another Beyond Dodos and Dinosaurs advisory board member: Karen Rader gave her lecture on “Thoughts in Things: a history of science perspective on museums in transition”. The visit that day involved two museums: The Norwegian Canning Museum and the Maritime Museum.

The master class session with lecturer Karen Rader and student Anne Mette Seines

Great sardine packing job by Faizah Zakaria at the Canning Museum

This event showed the fruitfulness of using environmental humanities approaches when thinking about how to display and interpret objects and social concerns.

Museum narratives are not neutral

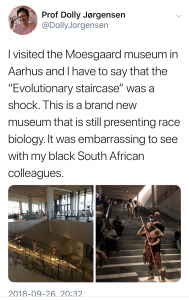

The Remembering Extinction project is concerned with the ways we narrate extinction histories and extinction future avoidance, particularly in museum settings. Because of that interest, I always pay attention to how narratives in museums are constructed.

When I visited the Moesgaard museum in Aarhus, Denmark, this week, the presented narrative of evolution in the Evolutionary Staircase struck me as particularly problematic. The staircase presents the change over time in humanoid species as an entry point to its archeological exhibits. In so doing, it is also dealing with the extinction of some ancestral species to modern humans (Homo sapiens).

I tweeted about this display and its racial overtones.

Because of my tweet, I received an invitation from the Moesgaard museum to further explain my concerns in a longer format. I share with you here the letter I wrote and sent to the Head of Exhibitions at the museum:

Dear Head of Exhibitions,

I was invited via a twitter exchange with the Moesgaard museum to explain my concerns about the exhibit in your central staircase (you can see my original tweet here). I visited the museum on Wednesday, 26 September, with four South African academic colleagues (three of African descent and one of settler descent). They were visibly aghast at the exhibit, as was I. This is why I, as an academic who analyses museum exhibition narratives, tweeted about the shocking presentation.

Let me start by saying that I understand that the individual models which have been displayed are based on accepted scientific findings – that is not my concern. What is concerning is that the display of those scientific findings has created a narrative that very clearly reinforces racial biology.

As I hope you are aware, the Scandinavian countries along with the rest of Europe have a long history of participation in biological sciences which attempted to explain “scientifically” why non-white peoples were inferior to white people. That argument rests on an idea that white skinned populations are more “civilised” than others and looks for morphological (as well as cultural) differences to explain why this is so. This is not an “old” argument — a 2018 study in Sweden showed that racial experiments on Sami continued into the 1950s.

With that in mind, look at the exhibit at Moesgaard. It very clearly shows dark skinned humanoids beginning with Lucy in Ethiopia getting lighter and lighter to the bottom where full-fledged homo sapiens is represented by a white Koelbjerg Man from Denmark. While these are individually true archaeological findings, the museum has created a spatial and temporal narrative through the display which has been labelled “Evolution”. This version of Evolution shows a movement from black to white. The museum has chosen specific findings to display out of a myriad of possibilities, and the choices have been constructed in a way which sits well with the arguments long espoused by racial biology. As a scholar working on the construction of narratives in museum displays, this is striking.

This narrative with light-skinned as the end point of evolution is not the only one which could have been constructed. Instead of ending on the Koelbjerg Man, the museum could have instead shown concurrently a variety of human finds from the Stone Age across the world – which would have clearly shown diversity in skin tones. It is not as if the museum is showing all Denmark specimens – you start with Lucy from Ethiopia and move through global finds before then. So why limit the conclusion of evolution to a find from Denmark? By making this choice, the museum is clearly aligning itself with a narrative of evolution that puts lighter skin higher on the evolutionary ladder.

Museums are never neutral. The way we display our science in museums tells a story to the visitor. And whether it was intentional or not, the story told in this particular exhibit is that human evolution progresses from dark to light. This is a dangerous narrative to reinforce.

Kindest regards,

Dolly Jørgensen

Professor of History